by Beth Dolinar, Contributing Writer, Luminari

Growing up in a little town south of Pittsburgh, my days were filled with neighborhood kids and outside games. There were always enough of us to put together a decent game of kickball or whiffle ball. When families went on vacation and our numbers dwindled, we settled for yard games like “statues” and a tag game called “colored eggs.”

And when winter came, my sisters and I would stay inside and play jacks, that game of speed and manual dexterity that seemed only ever to be undertaken by girls. We would hijack our mother’s kitchen linoleum and do a few dozen rounds of tossing the rubber ball and scooping up the metal jacks. Sometimes we were careless and left a stray jack on the floor, causing our mother to yelp as she stepped on it.

Meanwhile, the neighborhood boys were outside, playing marbles in the dirt. I only learned of this recently, as I came to understand the game of marbles.

I have spent the past six months filming and producing a documentary about the competitive game of marbles. For years, Pittsburgh has been a powerhouse, with local children winning national championships dozens of times over the past decades. Compared to other games and sports, the marbles community here is small, but it’s mighty. And its players are as serious about the game as any student athlete is about a school sport.

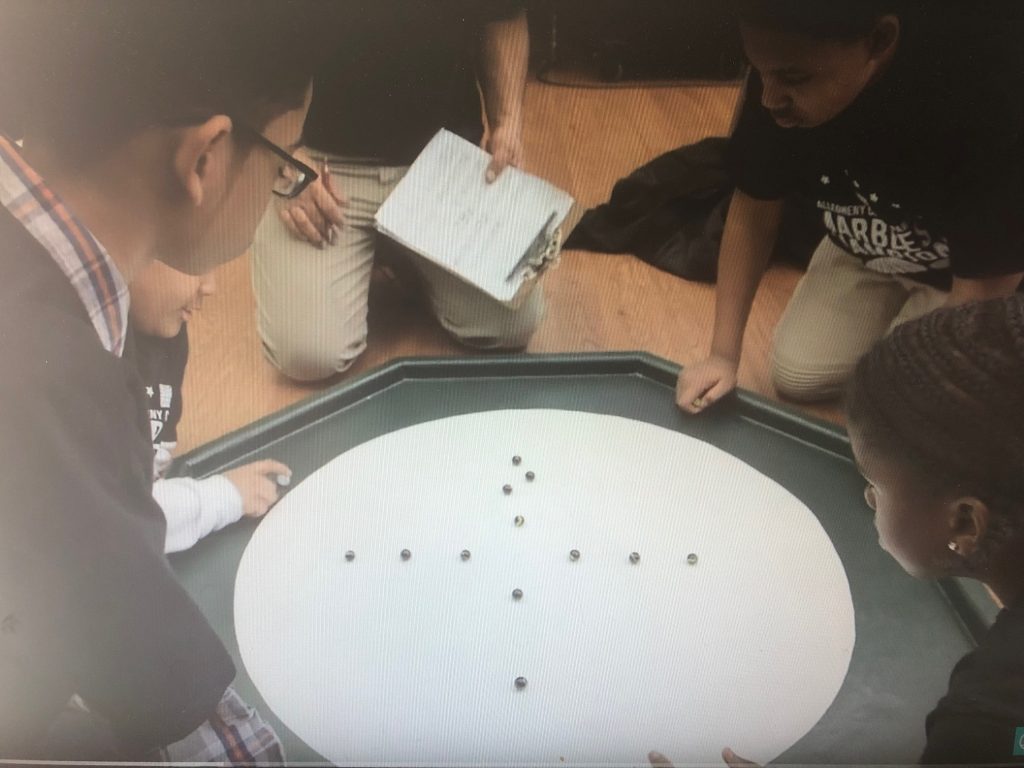

Marbles is a game that’s been untouched by technology. It has been played the same way, with the same rules and equipment, for probably hundreds of years. During the Great Depression, when families couldn’t afford toys or even a bat and ball, they could afford a bag of marbles. Kids would scratch a wide circle in the dirt, spill out the marbles, and play. The point of the game, called Ringer, is to use a shooter marble to knock the 13 smaller marbles out of the ring.

Until I started work on the film, the only thing I knew about the game was what I saw in a scene from “Little House on the Prairie” when Laura and her classmates play in the school yard. Not much has changed since the 1870s: kids fold themselves onto the ring, lean way forward, put the marble in the crook of their thumb, and push. I noticed that some of the best players tend to stick out their tongues as they do this. Maybe it helps.

Local champions go to the nationals, which have been held on the beach in Wildwood, New Jersey each June for going on a hundred years. There, on ten rings spread out under the baking sun, the kids play game after game. Some get injuries, including scraped knees and painful thumb blisters.

As a producer, I’m always amazed at what I don’t know. As my photographer and I worked our way through countless film shoots and hours more of editing, I thought about all the ways in which we humans amuse ourselves, connect with each other and express our innate competitive spirit. Funny, but I arrived at our first film shoot in March having never shot a marble.

Finally, at our last film shoot in September, as we were interviewing a man who had made it to the finals when he was 14, he asked if I wanted to try to shoot one.

I bent onto the ring, put the shooter marble in the bend of my thumb and gave it a push. It rolled pathetically toward one small marble and stopped. As I stood up, I realized I’d stuck my tongue out. It didn’t help.

Beth’s documentary “All the Marbles” will premiere on WQED-TV on October 17 at 8:00 p.m.

***

About the author: Beth Dolinar is a writer, Emmy-award winning producer, and public speaker. She writes a popular column for the Washington “Observer-Reporter.” She is a contributing producer of documentary length programming for WQED-TV on a wide range of topics and currently teaches as an adjunct faculty member at Robert Morris University. Beth has a son and a daughter. She is an avid yoga devotee, cyclist and reader. Beth says she types like lightning but reads slowly — because she likes a really good sentence.

About the author: Beth Dolinar is a writer, Emmy-award winning producer, and public speaker. She writes a popular column for the Washington “Observer-Reporter.” She is a contributing producer of documentary length programming for WQED-TV on a wide range of topics and currently teaches as an adjunct faculty member at Robert Morris University. Beth has a son and a daughter. She is an avid yoga devotee, cyclist and reader. Beth says she types like lightning but reads slowly — because she likes a really good sentence.